Note: My husband and I are spending a month in and around Medellin. Our Colombian daughter-in-law is here with her family and her two young children. She is sitting out the Minnesota winter and completing a project of building a simple house in a small lovely village above Medellin called San Pedro de los Milagros. We spent the first five days in Medellin, as tourists. This is the first of weekly posts about this amazing city and country. Our family connections and the focus of time have helped us to have a more immersive experience than on other trips where we were strictly tourists.

A common stop on the Medellin tourist train is the Graffiti Tour. There are many companies offering it. My husband Phil chose one called Toucan Café because the website stressed the importance of sustainable tourism, using local guides from the neighborhood who would speak in Spanish with an accompanying translator.

The night before the tour we had sat across the table from a young UK couple who had “done” the graffiti tour that day. I asked if they had a guide. They said no; they had just followed a walking guide in a travel book. Ordinarily I am one to DIY, but I am really glad I didn’t.

Our tour guide took us on an historical and political journey filled with terror, escape, conflict, murder, cover-ups, reorganization, and, finally, social transformation. And, we saw some dynamite art and ate the best and most sophisticated mango popcicle along the way.

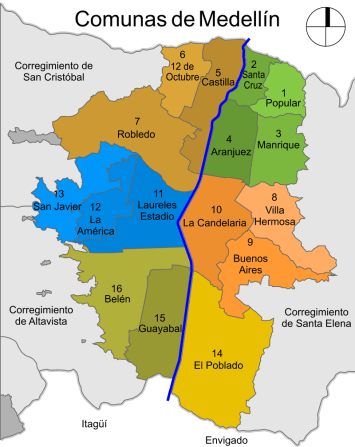

Our guide for the day was a member of a hip-hop collective in the neighborhood called Casa Kolacho. It was named in honor of a former member who was murdered. Our guide’s handle was Fury. She was translated into English by a Toucan Café staff member. She gave a Peoples’ history of Comuna 13, or San Javier, the neighborhood where the tour took place. It began as a shantytown on a steep hillside on the west side of Medellin.

Until recently the foothills with their spectacular mountain and city views have been the province of the poor. Armed violence began in the mid 20th century in rural areas of Colombia and especially in Choco, which is home to a large number of Colombians of African descent and has many natural resources to fight over. In 1946 the rural village on the western edge of Medellin began turning into a residential area attracting poor immigrants. In the 1970s and 80s in particular, people from Choco started coming into the western edge of Medellin in order to escape the violence. They built simple homes on top of each other perched precipitously on the hillside in an anarchic fashion. They were ignored by the Medellin government and hassled by the police. Gradually self-organization began to arise, first in the form of drug-trade oriented gangs, and then in the form of guerilla bands who acted as unofficial law and order and kept the cartel gangs at bay. Graffiti during those times reflected the territorial struggles and violence of this no-go area.

Around the time of the American Presidency of George W. Bush, a refreshed post-9/11 belligerency grew toward perceived foreign enemies. Anti-imperialism and support for socialism was growing in Latin America, and insurgencies in Colombia and elsewhere were viewed as threats to the U.S.’s economic interests. The former mayor of Medellin Alfaro Uribe was elected President of Colombia in 2002. His ties to Pablo Escobar and drug cartels made him an eager ally of Bush in rooting out the guerillas in Comuna 13 and elsewhere. At first military and militias would storm into Comuna 13 looking for guerillas, but the warren of houses with their mysterious pathways made it much easier for fighters to leave Comuna 13 behind and flee over the mountains to the west.

Frustration and anger mounted and in October a massive attack on Comuna 13 was launched called Project Orion. Mass indiscriminate shootings took place, with the aid of US Blackhawk helicopters overhead. The government admitted to 100 deaths, but the neighborhood believes it was closer to 300. The bodies were buried in a mass grave on an empty part of the mountainside and covered up. Even now forensic scientists are examining the site to get closer to the truth. The attack spurred community protests which have gradually evolved into more peaceful protests over repression and lack of concern for the community. During that period Comuna 13 had some of the highest per capita death rates in the world.

In the last decade, following the death of Pablo Escobar and defeat of the FARC in most areas, there has also been new progressive leadership in the government of Medellin with a different approach to bringing peace and justice to Comuna 13. Several important infrastructure elements have been built to recognize the needs of the community for work and access to the central city. I have reported more about this in a previous post. This story is about what ordinary people have done and are doing to transform themselves and their neighborhood into one of pride, self-reliance and joy.

Fury credits hip hop culture for providing the four elements of social development: DJ-ing, rap, breakdance and graffiti. Young men (primarily) who had previously been fighters or drug runners have a new identity as members of politicized hip-hop communities.

They spin music, invent lyrics, form breakdance squads to perform for the tourists, and create magnificent wall murals that are often political and metaphorical statements, as well as celebrations of the transformation that is being made. They also take regular jobs below in the city center and stay longer in school. We tourists see many young people walking by with Comuna 13 pride T-shirts. Street life is bustling with food, little shops, playgrounds and mini parks. Lots of people head up and down the 6 new outdoor, covered escalators that make the trip to the city center and back doable at any age or ability. At the end of the tour we visited Casa Kolacho to see hip-hop culture in action. There was plenty of spray paint at the ready.  Fury led us out the door and across a little bridge to a large empty black board. We were each given a turn to spray paint our tag. Fast, before the police catch you! Can you tell which one is mine? All agreed mine was the best.

Fury led us out the door and across a little bridge to a large empty black board. We were each given a turn to spray paint our tag. Fast, before the police catch you! Can you tell which one is mine? All agreed mine was the best.

This is no utopia, but a creeping revolution. People make their own power through collective and politicized action and do not look to government or police to take care of them. There are still gangs but our guide said they engage in local turf battles, rather than armed conflict. I am inspired to see this model of transformation from endless armed struggle and organized crime as the only options for the poor to self-aware, class conscious self-expression and personal agency. We need more of this in the US.

You have a future in grafitti art fo sho.

LikeLike

Ya think? My first chalk graffiti foray pist retirement, we were busred immediately.

LikeLike