Guest blogger: Lily White, who just spent one month in Argentina. Thanks, sis!

Sometime between the 1970s and 80s, hitchhiking fell out of fashion in the USA. Signs began popping-up along the entrance ramps to highways, and stories of dangerous hitchhikers circulated around our small Midwestern town. My mother and Aunt Dorothy cut cautionary articles from the Aurora Beacon News and stuck them to the refrigerator. Popular horror films made it clear that offering a ride to a stranger or worse, getting a ride with a stranger, was a guarantee of getting raped or killed. Needless to say, I never dared it.

Later, I made some exceptions. After college, I hitchhiked in France because Europe seemed safe. Nothing bad could happen in the land of cheese and wine. A few years later, while playing saxophone with a band in Finland, I was running late for a sound check and stuck out my thumb on a whim. I was immediately picked up by a Finnish man in a Ford pick up truck blaring American country music. He was wearing cowboy boots and hat, and had an empty gun rack in the back of the cab.

“Where’s your gun?” I asked.

“Eees very difficult to buy guns in Finland.”

I got to the sound check on time, and got a good story out of it, which is perhaps the main reason that I am interested in this age-old custom. This time while traveling in Argentina.

January in South America is like July or August in North America. I knew this from books, but the reality of going from 0 to 97 degrees in January made my fingers swell. Packing proved a challenge as well, since my summer clothes barely fitted over my padded winter hips. In Argentina January is the beginning of their summer break and time for them to grab their maté cups and bulky thermoses, and head into the countryside.

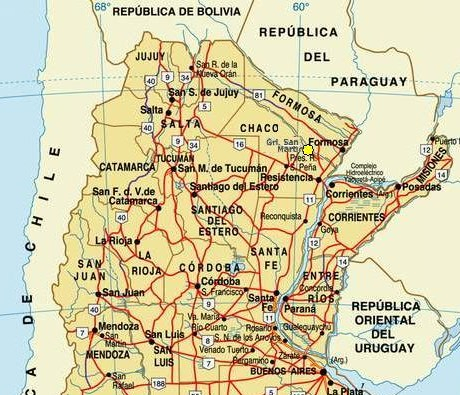

The provinces of Salta and Jujuy were not well known to me. Situated in the mountainous Northwest corner, they border on Bolivia and Paraguy. My husband and I drove up from the lush city of Salta in our rental car, watching the scenery turn from green to brown to red. Here, according to the guidebook, stores sell bags of coca leaves in order to combat the fatigue that comes from the high altitudes. Indeed, along the way, we picked up two Argentine women hitchhikers who had coca in their cheeks, and they let me try some. One woman opened a plastic bag containing what resembled bay leaves. I took a pinch of them and stuck them in my cheek as instructed. They quickly softened in my mouth, tasting a little like dirt. I waited for some sort of effect, but after ten minutes when I couldn’t figure out how to take a sip of water without gagging, I secreted the wet wad in a napkin and stuck it under the dash.

We’d gotten a tip to go to Humahuaca, a town 40 minutes north to see a market of indigenous handicrafts. That day I had dressed for a hot town in shorts and a T-shirt, but the market didn’t interest either one of us. We changed plans and decided to drive to the Sennaria del Hornocal, a colorful geological display about 50 minutes inland on a dirt road. To get out of town, we crossed the main bridge over the Rio Grande, a trickle of water traversing the center of a 200 ft. wide riverbed. “Not so grand, eh?” I said. In fact, every river we passed was similarly dry–the road and river often indistinguishable. “Maybe it only flows in the spring,” I said. According to our digital map, we were heading for Rt. 73, either to reach the mirador, or lookout, or the actual Sennaria de Hornocal. I couldn’t really tell since my map had little detail. Conrad was interested in the natural landscapes where he could practice his passion for rock-balancing. While I supported his new artistic endeavors, I didn’t really like to do it myself. I was more interested in culture, but it was unclear exactly how I could experience any of it it with my weak Spanish.

Very soon we came across several groups of hitchhikers. Conrad stopped the car in front of two young men carrying a cardboard sign reading, Hornocal. Hay Maté –“there is maté.” I was a little surprised he didn’t pull over 20 yards further where a group of three 18-year-old girls in miniskirts and cut offs were hitch hiking along the same road. One of the guys spoke no English, but the other had done a stint at a ski resort in Park City, Utah some years back, so Guido, became the spokesman. Santiago and Guido were students in Corrientes– one studying to be a lawyer and the other a physiotherapist. “We are patients!” Conrad exclaimed. Our little car, a VW Up!, chugged up the rocky road, I was happy being in the front seat, since it was so rough going.

I was praying that we wouldn’t get a flat since it would be difficult to change a tire on this hot and narrow road. Occasionally, 4-wheel drive trucks would speed past us raising a cloud of dust. For this reason, Conrad put on the air conditioning which allowed us to keep the windows closed and the car dust free.

Meanwhile, Guido made polite conversation. Where were we from? Where have we been in Argentina? What did we think of the Argentinians? We told him of our journey to Patagonia, and how we were very impressed with the spirit of the people we met along the way. Conrad repeated something we had heard from another hitchhiker on the previous day.

“Argentines are like children,” he said, and I hoped that this would not prove insulting to our passengers. There was a quiet murmuring of Spanish as Guido translated to his friend. Conrad went on to explain, “They are always happy to enjoy life, and are curious about the world.” That seemed to satisfy them and I breathed a small sigh of relief.

Soon we began to climb a series of steep switchbacks. In narrow areas, we would have to pull over to accommodate other larger vehicles passing us on the way down. I hoped the trip was worth the trouble, but we didn’t have anything else to do. I had wanted to visit some caves in the area, but since the cave was on indigenous Omaguaca land, a tour guide was required. Conrad was more interested in being on his own to balance rocks.

“How long, does it take to be lawyer in America?” asked Santiago, the law student.

“2 to 3 years.” said Conrad, which led to a flurry of conversation from the backseat. “Though, that’s after 4 years of college,’ he went on to say.

“Aah.”

Then came the question. “How much does it cost to go to college in the USA?”

“Hmm, that depends…if there is no financial aid, and the parents make a lot of money, then it can cost upwards of $60 grand a year!” The boys exclaimed in disbelief! We enjoyed the dramatic effect for a little longer and then added,

“But, really, if you go to a state college, then you could get away with it costing $20 grand a year, or much less, depending on the parent’s income.”

After some multiplication to get the amount in pesos, there was not the relief we expected.

“If I had 100 thousand dollars, I would travel for ten years,” said Guido.

I laughed, but my smile began to feel strained. Our daughter would be starting college in the fall and it was, indeed, a shitload of money. In Argentina, university is free and I wondered how the US of A could get it so wrong. Even the many Venezuelans who had immigrated here could attend for free, which was an amazing opportunity, given that they had little left in their home country to go back to.

I glanced at the satellite readout on the phone, and saw we were now at 12,000 feet. Conrad was doing a fine job navigating the blind curves on the pitted road. Our little VW UP! Chugged along, air conditioning blasting.

“Only 3 more switchbacks,” I said, when suddenly the car stopped. “What are you doing?” I asked Conrad.

He didn’t respond as the car began sliding backwards. It took me a few seconds to figure out that he wasn’t simply pulling over to let a big bus go by. We were without power and he was trying to control our backwards slide so that we would not head over a cliff. Eventually we came to rest on a somewhat flatter and wider area of the road.

We climbed out of the car, and for the first time, I took a real look at our passengers’ faces. They both seemed so young. I felt guilty that Guido and Santiago were stuck with us and our lame VW UP! They would have been better off getting a ride in a pickup truck–or at least with people smart enough not run the air conditioner while climbing a mountain. Big mistake.

“If you guys want to continue walking, we won’t mind,” Conrad said. “There’s only 5 km to go.”

“We will stay,” said Santiago. “We start with you, and so we must finish what we start.”

This declaration made me inexplicably happy. Instead of being stuck together with just the two of us, we were part of a gang. Had my husband and I been alone, there would have been far too much blame going around. Hitchhikers were the perfect buffer. Instead of having bad luck, we were having an experience.

There was nothing else to do but wait for it to cool down. Santiago broke out the cold maté and Conrad wandered off to stack rocks. Cold maté proved too bitter for me. I watched as Guido pinned a friendship bracelet to his pant leg and began weaving. Earlier in the trip, he had shown me a collection of dusty woven bracelets of varying widths and colors, and asked me if I wanted one. Now I understood that he was making them to help fund their trip.

45 minutes later the temperature gauge read 90 degrees which was, apparently, normal. We added a liter and a half of cold water, which was a better use for it than making maté. We headed back up the mountain with the windows open this time.

Rounding the top of the hill, we saw what the guide books had promised: a spectacular view of the multihued Hornocal mountain face; a psychedelic hounds-tooth pattern of reds, pinks, greens, browns, and greys. I was glad to finally see it, and on a sunny day. At 14,700 ft. the air was chilly, and I was still in my market day T-shirt, so I dug out my beach towel and wrapped it around my shoulders. It was 1:30. We bought a couple empanadas, and said hasta luego to our hitchhiker friends, promising in a non-committal way that if we were still here, we would definitely give them a ride back down. They hiked out across the hills in a northeast direction carrying their thermos.

Rounding the top of the hill, we saw what the guide books had promised: a spectacular view of the multihued Hornocal mountain face; a psychedelic hounds-tooth pattern of reds, pinks, greens, browns, and greys. I was glad to finally see it, and on a sunny day. At 14,700 ft. the air was chilly, and I was still in my market day T-shirt, so I dug out my beach towel and wrapped it around my shoulders. It was 1:30. We bought a couple empanadas, and said hasta luego to our hitchhiker friends, promising in a non-committal way that if we were still here, we would definitely give them a ride back down. They hiked out across the hills in a northeast direction carrying their thermos.

Conrad headed up behind the parking lot to find some rocks in the scrubby landscape, but it wasn’t easy. I hiked up past him a few hundred yards, thinking I might venture out across the hills, like our hitchhikers. I was quickly overcome with altitude fatigue. I wanted to sit or lie down and watch him stack, but the ground was littered with sharp rocks and cacti which made it impossible to get comfortable. If I folded up the beach towel to sit on, I was freezing, and if I wore the beach towel, I couldn’t sit down without risking a hole in my only pair of pants. I ended up returning to the UP! and getting out my 1200 page book by Kim Stanley Robinson. Between chapters I gazed out the windshield at the view as large clouds gathered overhead, casting shadows over the spectacular hills. It was still sunny where we were, but in the hills surrounding us grey sheets of rain brushed the mountaintops. A couple of lightning bolts forked across the sky and I wondered if Conrad was close to finishing. I looked back and saw him crouched with his camera which might mean that he was close to being done. If I could convince him he was in danger of being struck by lightning, maybe we could leave sooner.

I was getting colder, yet every time I looked back, I saw him starting a new sculpture. I should have been more patient, but I was getting sick of waiting around. I had to keep reminding myself of how many of my late night jazz sets Conrad had patiently sat through. I rolled up the windows to conserve heat and fell fast asleep. I don’t know how long I was out, but there was a knock on the glass, and I bolted awake to see Guido and Santiago’s smiling faces. Santiago grinned at me and handed me a quartz stone. I was happy to see them, and even happier to have an excuse to bother Conrad.

I was getting colder, yet every time I looked back, I saw him starting a new sculpture. I should have been more patient, but I was getting sick of waiting around. I had to keep reminding myself of how many of my late night jazz sets Conrad had patiently sat through. I rolled up the windows to conserve heat and fell fast asleep. I don’t know how long I was out, but there was a knock on the glass, and I bolted awake to see Guido and Santiago’s smiling faces. Santiago grinned at me and handed me a quartz stone. I was happy to see them, and even happier to have an excuse to bother Conrad.

“Hey, Conrad,” I yelled, “the boys are back! Are you almost done?” He said he was, and I was again grateful for the buffering powers of our hitchhikers.

By 6:30 pm there were only a few cars left in the lot. With seemingly boundless energy, Conrad drove the whole 50 minutes down the mountain. As we neared the town, traffic had come to a halt. 30 cars and buses were at a standstill in the middle of nowhere and we couldn’t fathom what the problem could be. We got out and walked to the front of the line of cars and saw that the dry river that we had easily crossed in the morning was now a torrent of brown water 70 feet wide. The UP! would never make it across.

There was a gathering of other drivers and passengers watching the scene. The atmosphere was festive as people chatted among themselves, played ball and drank maté. A police truck came by and I naively assumed that they would take charge and tell us what to do. But, it turned out that they too were stuck. We watched as a man repeatedly dragged the bucket of a bright yellow front-loader backwards across the river. The engine and the back-up beeping compounded the roar of the river. They couldn’t stop the river, but they could make the riverbed relatively even.

“That’s his job!” yelled Santiago over the cacophony.

After many trips back and forth with the big yellow earthmover, a couple of the larger buses and SUVs drove across. When the fifth car, another tiny rental car like ours, made it without getting stuck, we all cheered. People slowly returned to their vehicles, the line of cars moved up, and we waited again for the front-loader to make several more passes. An hour later, it was our turn, and with Conrad in the driver’s seat we made it to the other side. Our joy was short-lived since a quarter mile down the road, there was another flood. The river had jumped its banks and taken over the road, twisting and turning through rocks and mud. This one seemed far worse.

By this time, it was 8:30 and the sun was starting to go down. I couldn’t understand why Guido and Santiago stuck around, since they could have easily taken their back packs and hoofed it to their campsite. I was starving and worried that I would have to sleep in the cold car all night. Conrad wandered away again, Guido got out his bracelets, and Santiago and I stood under some bean trees not saying much. People didn’t seem nearly as freaked out as they should be. To no one in particular, I said, “If he goes off to stack rocks, now, I am asking for a divorce.” Just then I saw him in his orange shirt as he picked his way through the flood in his bare feet. The water was up to his shins. What on earth was he doing? He made it to the far side of the flood where there was a sandy embankment where a smaller dump truck was doing something. There, he began searching for rocks. Like a rat following the Pied Piper, Guido went after him, discarding his backpack and bracelets behind on the ground near me. No wonder they were so filthy. Was no one but me concerned about the car? In the distance, I could see the two of them as they began to balance one rock on top of another while an audience of children and stray dogs looked on. Santiago looked at me and shrugged, and suddenly everything seemed all right. After all, we had each other and we had maté.

Hi there readers! I have a couple of corrections to the post. I meant to say that Jujuy borders on Bolivia and Paraguay NOT Peru. Also, in the following paragraph, I wrote I got a “tip” to go to Humahuaca, not a “trip.” Thanks for reading in any case! –Lily White

LikeLike

WHAT A GUY! WHAT A GAL! WHAT AN ADVENTURE!

>

LikeLike

fixed

LikeLike