This summer I agreed to go on a six day, five night canoe trip into the Quetico National Park in Ontario, CA, in early September. It is just across the border from the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) in northern Minnesota, with a similar landscape of lakes, rivers, and islands, with portages connecting them or bypassing them as needed. Since the Boundary Waters are now threatened by proposed nickel and mercury mining next door, it’s a good time to share with folks who have not experienced real wilderness, what is the big deal.

First, what is considered a wilderness? According to the 1964 US Wilderness Act a wilderness has these characteristics: (1) generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; (2) has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; (3) has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient size as to make practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition; and (4) may also contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value. Two percent of the land in the lower 48 is wilderness, and it is disappearing around the world at an alarming rate. It is easy to see why adventurers, canoe outfitters, and nature lovers would want to save the wilderness, but why would urbanites like me care? This trip has reminded me of what the northern wilderness gives us.

My husband is an avid long distance hiker and the group included four of his hiking friends. All are 6 to 16 years younger than I and all are athletes. Although I have loved this rare part of the world, I was hesitant to commit because it had been 10 years since my last foray into the BWCAW. That trip was by solo kayaks, so I had to portage my own boat. The portages were very slippery and rocky and I was quite certain I would end up with a broken ankle or worse. This trip would be with canoes, so my husband Phil would portage the canoe and I would help to schlep the heavy packs and miscellany. My intrepid canoer, aikido expert, and hiker friend Kathy promised me that this would not be one of those 100 mile forced marches and encouraged me to try it. I said yes.

Phil and I spent a couple of months training for canoe paddling in our closest lake. Paddling uses different muscles and stance than kayaking, which has been my boat of choice for twenty years. Thanks to a neighbor with an old aluminum canoe moored by the shore of Cedar Lake, we could bike the mile to the lake two times a week, with our new light paddles strapped to the frame, wearing our life jackets, and put in an hour or two without taking an entire morning off. Each week we noticed a strengthening of our paddling muscles and improvements in our bracing and steering.

On September 12th we headed north to bivouac in Grand Marais at Kathy’s house before heading north. We packed and repacked our meals, cooking equipment, clothing for all weather, tents, sleeping bags and pads into waterproof bags weighing up to 40 pounds.  On the 13th we drove down the Gunflint Trail to a canoe outfitter near the Canadian border. We rented a nice light Kevlar 17 footer. We all opted to be ferried for the first half hour over a very large lake on a very windy day and dropped off on a border island on the lee side of Cache Bay.

On the 13th we drove down the Gunflint Trail to a canoe outfitter near the Canadian border. We rented a nice light Kevlar 17 footer. We all opted to be ferried for the first half hour over a very large lake on a very windy day and dropped off on a border island on the lee side of Cache Bay.

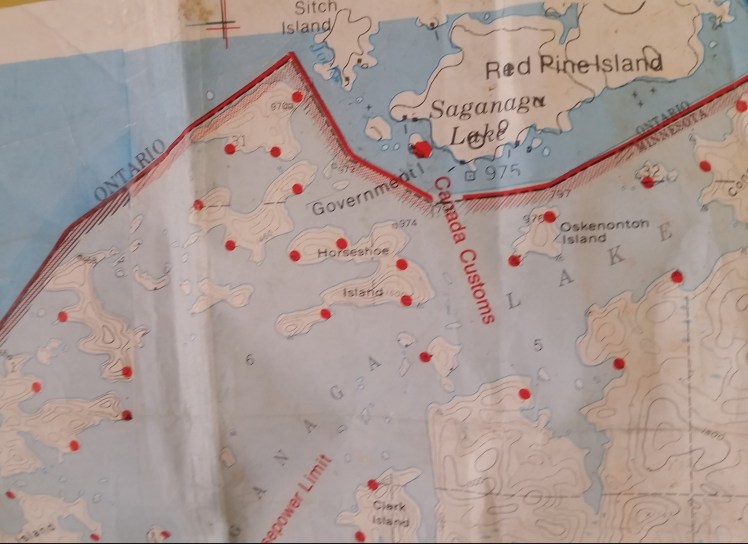

First lesson: This is what open borders looks like. There is no electrified fence separating the American from the Canadian side of Cache Bay, or even any sign denoting national boundaries. No passports required. Only a temporary authorization pass to cross over and stay in the Quetico. Both sides look exactly the same. Same birds, same trees, same rocks. Same no people.

First lesson: This is what open borders looks like. There is no electrified fence separating the American from the Canadian side of Cache Bay, or even any sign denoting national boundaries. No passports required. Only a temporary authorization pass to cross over and stay in the Quetico. Both sides look exactly the same. Same birds, same trees, same rocks. Same no people.

Second lesson: Map reading and orienteering.  No GPS, no cell signals. Only some detailed maps showing campsites by dots and portages by a line between two bodies of water with the length noted in rods. Imagine aliens knocked out our satellite and electrical systems and everyone but we six were taken away in their ships to act as slave labor in their oxygen mines. Let me just say that I was grateful that two of us were adept map readers, leading to the Third lesson: Trust. What if our map readers made mistakes? What if we fell off the maps we had purchased? It sounds dramatic, but actually the aliens had not knocked out all the satellites.

No GPS, no cell signals. Only some detailed maps showing campsites by dots and portages by a line between two bodies of water with the length noted in rods. Imagine aliens knocked out our satellite and electrical systems and everyone but we six were taken away in their ships to act as slave labor in their oxygen mines. Let me just say that I was grateful that two of us were adept map readers, leading to the Third lesson: Trust. What if our map readers made mistakes? What if we fell off the maps we had purchased? It sounds dramatic, but actually the aliens had not knocked out all the satellites.

One of us had a Sat phone, which uses older iridium satellites, and he could call in an emergency for help (assuming the aliens had left some human helpers behind). Two of us brought fishing gear so we wouldn’t starve. Appreciate expertise in the wild. Your life may depend on it.

Fourth lesson: Body awareness. I soon discovered that the paddling stance I had perfected during summer training—knees on the floor of the canoe and butt perched on the edge of the seat—was not possible because this canoe’s seats were set too low. I had to find a new way of bracing to preserve the small of my back while I paddled for five hours. Done! Then at the first long portage, I stopped by some boulders to rearrange the weight of the pack on my shoulders. I balanced the pack on a rock, slipped my arms through the straps and then stood up to throw the pack up so the straps would be fully on my shoulders. But the weight of the pack threw me over and I smacked my head on a rock. The bruise is still painful a week later, but otherwise no harm done.  Keep eyes on the uneven ground at all times. Never assume I won’t slip when ascending or descending a boulder with dampness or moss. Wear Keen water sandals which grip when nothing else does, but bring duct tape for when one of the soles starts to fall off.

Keep eyes on the uneven ground at all times. Never assume I won’t slip when ascending or descending a boulder with dampness or moss. Wear Keen water sandals which grip when nothing else does, but bring duct tape for when one of the soles starts to fall off.

We reached our first island campsite by 5 pm and everyone began their assigned tasks. Put up the tent and rain fly, blow up mats, change from wet water shoes and socks into dry camp wear. Get lake water and start the drip filtration system. Find the plastic glasses and decide where the best spot for cocktail hour should be. Skinny dip if weather permits. Drip dry. Designated cook starts his or her process as the kindling lights up. Put on bug dope if necessary. Exclaim about the meal. Tell stories. Hang the food packs. Dowse the fire and clean up. Go into the tent at 9 pm, exhausted. Read the Kindle by headlamp. Try to go to sleep. Hear noises, wake up to pouring rain or fierce wind. Go back to sleep. Wake up in the morning. Take the small trowel, toilet paper and hand sanitizer some place away from camp. Dig a hole. Squat. Do my business. Cover. Place a rock to mark the spot. Back to tent. Somebody cooks and cleans up. Garbage is packed up into zip lock bags with the food pack. Leave no trace. Everything done the night before is reversed and packed tightly where it was before so it can be found easily the next day.

Fifth lesson: Don’t be sloppy. There is no garbage can to drop something into and forget. There is only so much toilet paper in the world. If I forget where my inhaler is, I get tired a lot faster. Same for bug dope. Spilled food attracts animals. Don’t let the sleeping bags get wet. Save dry warm clothes for sudden cold weather at night. Had I joined the military, perhaps I would already have learned this lesson.

The weather during our six days ranged from a hot dry windy 80, still but cloudy 75, fierce dry night wind, a misty 65-70 with somewhat scary waves, more sun, semi-sun, torrential but warm night, and finally, a cold dry night followed by wind at our backs and cloud cover. Sixth lesson: I must live in the weather. Be prepared. I used every article of clothing I brought at least once, from naked skin to down vest and wool hat, Ikea poncho, tee shirt and shorts, and lined footless tights. I was never uncomfortable—too cold or too hot. I enjoyed having cool arms and legs, warm core, sweaty back, wet feet, misty eyeglasses, and temperate wind gusts on my face. Early September is a great time in the northern wilderness.

Seventh lesson: Untouched nature is beautiful and quiet. The pine forest has no buckthorn or other invasives, but a carpet of golden pine needles connects each tree and mulches between granite boulders. Red rose hips mimic the red dots signifying campsites on our maps. Lichens come in blues, lime green, sable brown, white, and pink. There is no polluted storm water to watch out for, no weeds to pull, no hose to run. The forest floor is soft with centuries of soil restoration. Fire has come and gone. Trees die, drop and turn into soil and homes for critters. Nobody cleans it up or hybridizes. Now and again a pileated woodpecker squawks or a loon calls, but not that often. Overhead or on a distant rock an eagle, vulture or heron casts a silent shadow.

Back in Minneapolis my mosquito bites are itching less. I woke up in my comfy bed with a sore back, which I never had in my tent on my pad. I checked our townhouse irrigation system to see how it had worked over the few hot days I missed here. Our landscape committee planned our fall clean up and started to plan for a more organic approach to caring for our beautiful but manicured townhome association landscape. We left everything on the basement floor to clean up over the next few days and started the washing machine. I took the garbage out. Then I wrote this post.

That looks like such an amazing, but challenging, trip. I loved how you added the lessons in there. And yeah I would bet it is quite important to know how to read your maps properly and be able to trust whoever was giving directions! haha Nice post 🙂

https://phoenixslife.com/

LikeLike

Great post. Full of useful information

LikeLike

Great post! As a fellow traveler, I’ll add the lesson that using all of your senses in the wilderness is useful for navigation and safe travels: the sudden feel of humidity in the air signals rain is nearby, paying attention to changes in the wind direction help keep you safe on water and land, and seeing the variation in the waters’ surface can add in navigation and knowing where the fish are. The wilderness affords us the opportunity to engage all our senses in a way that GPS mapping eliminates.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I treasure your description of pristine nature without invasive plants to weed, sounds to suppress

LikeLike